Most conversations about EVs pretty soon turn towards battery technology and charging times, but the electric motors that actually drive an EV rarely catch the limelight. That’s a shame, because the beating heart of a car, the engine, has traditionally been something drivers get excited about, so why should electric motors be any different?

An EV’s electric machine (to use the motor’s proper name – it works as a generator as well) is just as important as the battery in achieving the best possible range. Range directly relates to one crucial characteristic of electric motors: their phenomenal efficiency (ie how good they are at converting electrical energy into mechanical energy). Even the best combustion engines don’t do a great job in converting the energy in the fuel into torque, with only around one third of the fuel you put in the tank contributing to actually getting you down the road. Ouch. In contrast, a sophisticated EV’s electric machine can be more than 90% efficient.

The three main types of electric machine used for EVs are brushless asynchronous induction (Tesla Model S), brushed externally excited synchronous (Renault Zoe) and, by far the most common, brushless permanent magnet synchronous (Nissan Leaf, Tesla Model 3).

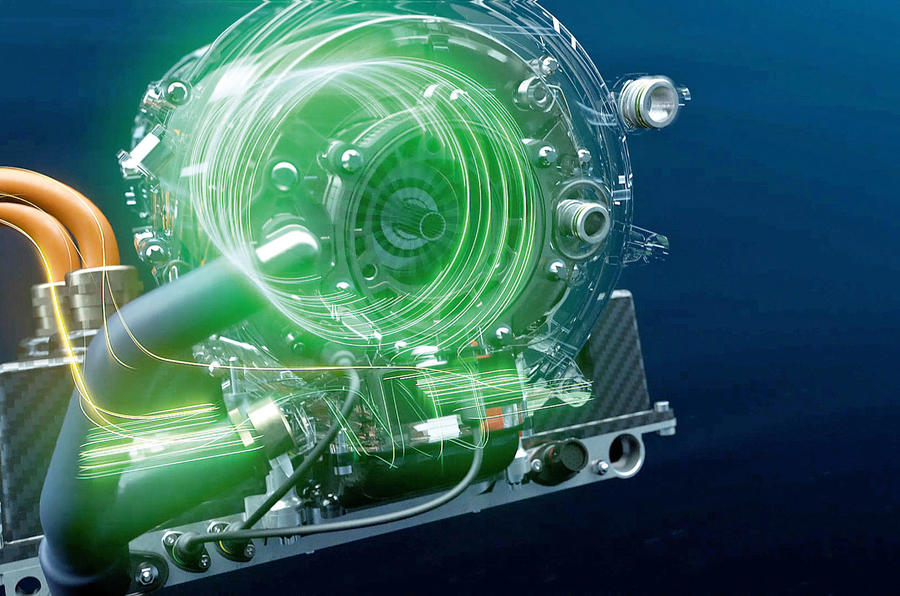

Permanent magnet and induction machines are mechanically similar. They both have a stator (static – it doesn’t move) consisting of electromagnetic coils arranged in a cylinder, and a rotor (it rotates) at the centre. In a permanent magnet machine, the rotor consists of powerful Neodymium ‘super’ magnets. When the stator’s electromagnets are switched on in sequence by a controller, a magnetic field rotates around the rotor like a merry-go-round. The rotor’s magnetic fields chase the moving fi eld at exactly the same – hence ‘synchronous’ – speed. The rotor turns.

In the other two types, both stator and rotor are made up of electromagnet coils and there are no permanent magnets. In the induction motor the merry-go-round stator fields ‘induce’ a current and magnetic field in the rotor windings by turning slightly faster (asynchronous) than the rotor turns. In the externally excited machine, the rotor coils are connected to a DC power source by a rotating electrical contact called a slip ring, to generate the magnetic field, so it works just like the permanent magnet machine.